Community, Colonialism, And Art - In Conversation With Rahul Varma

Photo: Entremise

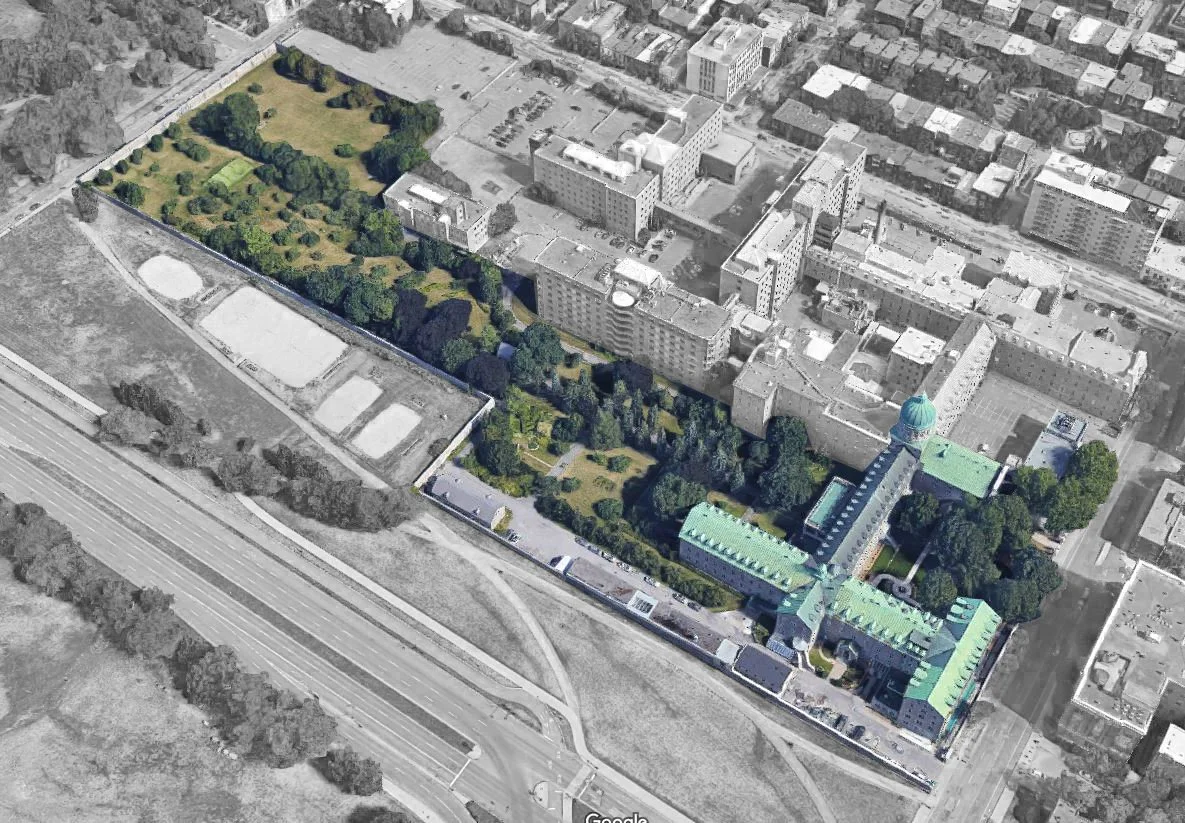

All high school students in Quebec learn about Jeanne Mance, the first nurse in New France. In 1645, she founded the first hospital in what would become Montreal, Hôtel-Dieu de Ville-Marie. The first 3 Religious Hospitallers of Saint Joseph arrived from France in 1659 to help run the hospital. Together they founded nursing schools, studied pharmacology, and ran the Hôtel-Dieu pharmacy on the same grounds, becoming some of the first pharmacists in New France. The story of Jeanne Mance is taught with reverence, and she is something of a Mother-Saint in our local lore.

As for the location of that first hospital, I'd never given it any thought. As much as I love Montreal, I must admit that I take our many historical sites for granted. It turns out that members of the same congregation kept the hospital running for the next 300 years (no big deal) The hospital itself burned down 3 times between 1695 and 1734, but they kept rebuilding. Many medical milestones took place on the premises, including the world's first removal of a kidney (1868), the first identification of an AIDS patient in Canada (1979), and the world's first robotically assisted surgery (1993). The hospital closed in 2017, bought in part by the City of Montreal with a plan to transition the site into a “shared public space”. The reinvented space, now called the Cité-des-Hospitalières, had strict guidelines when considering who would occupy the space, including preserving the spirit of the grounds, and responding to the needs of the community. They wanted custodians not tenants.

Walking into the building in 2024 feels unreal, like a perfectly suited stage for a period piece. The hallways feel both hallowed and distinguished, crafted with a care and skill that have been lost to modernity. It makes sense then that this is the building I arrive at to interview Rahul Varma, Artistic Director of Teesri Duniya Theatre. He co-founded the company along with Rana Bose back in 1981, and the theatre has been walking the talk ever since, proving that they're interested in more than entertainment.

Photo: Entremise

“There's a difference between being an entertainer for the sake of entertaining or an engager for the sake of something more. I prefer the latter,” Rahul tells me with a warm smile. “From the very inception, the idea that the art has to have a meaning was important, but I think that I was also reacting to certain situations. And what I was reacting to when I came here to this country [in 1975], was that things were very one type.”

Arriving from his native India, he was struck by the homogeneous nature of our art scene. What we were portraying was disconnected from the actual makeup of our country, disassociated from the stories we really had to tell.

“The stage was only one type of people and one type of activity…If everything was monochromatic white, and we were all telling the same story from the Eurocentric perspective, we were not talking about the real Canada that we were living in…Well, we're going to start a company which will represent everybody, and it will have a notion of Canada, which is a composite nation.”

The only difference in arts at the time was language, either French or English, but both were white and Eurocentric. For the first couple of years the company produced plays in Hindi. Such a seemingly simple choice, to create art in their mother tongue, was a giant leap for local artistic offerings. From there the conscious decision was made that they had to avoid replicating the problem they were criticizing. Realistically, they couldn't exclude white people - or countless other groups - from the story, because they were part of Canada's tapestry, too. That evolution came with Job Stealer, a short play they performed in a parking lot on Ontario and St. Laurent.

“Fourteen different nationalities were represented, and that gave a much wider impression of who we were as a country. So interculturalism, multiculturalism, has been a part of the founding of the company from the very beginning. But then, at the same time, displaying the diversity, displaying the colour of skin, playing with cultural identity, is not the only thing. You had to go beyond that. We had to bring some progressive content into what we do. That's why we began to tell more meaningful stories…Any form of art is a medium of communication. If we have the choice to communicate, why don't we communicate something which is significant?”

Not fitting in with any of the established groups, Teesri Duniya had no public funding at first. While grants were widely available, the company didn't check the boxes necessary to satisfy those holding the purse strings.

“Part of the reason was that my experience, and my co-founder Rana Bose's experience, were not very Eurocentric experiences. We were still regarded on the margins of society. There was European art, European Canadian art, and what anybody else was doing was not well supported.”

Rahul tells me that there was funding for “exoticized events” like festivals, food shows, and costume parades, but nothing with an “aesthetic base”. He took up the flag for funding more diverse art, working on a committee to change the standards, fundamentally opening the door for the myriad of publicly funded art that followed.

“We had to have a struggle for that…There are people other than two types, and they all practice their art in different ways. And there should be accommodation and a provision for that.”

The committee recommended racial equality in the arts, and the Canada Arts Council agreed. The equality extended to other marginalized communities, including LGBTQ.

“I saw this statistic somewhere…that after the mid 90’s, when these new rules were implemented in practice, more than 50 culturally diverse organizations sprung up all across the country.”

Another shock to Rahul’s sense of community came in the form of the separatist movement that was beginning to take shape in the ‘70s. Dickering over the imagined lines on already stolen land was a thought experiment beyond comprehension, a misconception we still struggle with.

“That didn't make any sense to me. [Now] we are reading the land acknowledgement and making a pronouncement at the start of all events that we acknowledge we are a settler colonial state, and that there are people who lived here before us. So it became a very ridiculous idea to seek sovereignty on a land that you have actually colonized. It was the absurd battle of the ex-colonialist to have an upper hand…You can't gain sovereignty in a country where you have come to live as a shared citizen… It's important to acknowledge, it's necessary for us to begin to speak about it, but at the same time, what is more important is to understand what it really means to say that we came here as settlers, I'm a settler myself, I acknowledge that it means we dispossessed some other people who were here before us, and it means that there is a pipeline going through their land of which they do not have the control. It means there are missing and murdered indigenous women, and there is no justice rendered to them. It means the unmarked graves, and the fear that more unmarked graves will appear…It means that the treaties have been broken. It means that the Pope would lie, and nobody would say anything…And then it means that right now as I'm talking to you, there's a war going on in Palestine. It's a real case of genocide and our politicians have said that this is a war against Hamas. Well, Hamas was born after the colonization of Palestine…If you understand the colonization in Canada, you should have no difficulty in acknowledging the fact that 75 years ago, Palestine was colonized. That's the contradiction. So I have to question: do we really understand what settler colonialism is? and are we really willing to decolonize our country? Is a mere statement of acknowledgement going to lead us to decolonization? No. In this particular case, it's obvious, I mean, every indicator is telling us what is happening, that the genocide is happening. Children are starving. No ceasefire has been called, and the governments are mute, the art community is mute. But we've spoken about that since October 7.”

Working with various groups including members of Independent Jewish Voices, Teesri is committed to the cause, and dedicated to the need for conscious discourse. They produced My Name is Rachel Corrie, a play composed of diary entries and emails of activist Rachel Corrie who was killed by an Israeli soldier. They also hosted Gaza Monologues: Voices Unveiled For Peace & Truth with the tagline Let's keep the conversation going. Their multidisciplinary exhibit Cocoons Between Earth and Heaven by artist The Babylonian was about the lives of children in Gaza. It included visual arts as well as poetry for Palestine, and a subsequent discussion with attendees.

“It's a mobilization right?…[Our] slogan says change the word one play at a time but what it means is to mobilize the public opinion towards social justice and towards peace… You can already see a shift beginning to take place, and I think we played some role in the transformation…But we spoke up; many did not.”

Rahul is the embodiment of think global, act local, and Teesri Duniya along with him. While their mandate begins with meaningful art, their mission takes them beyond the stage, enriching the community with an ever-changing schedule of activities. While their previous locations (often shared or donated spaces) left them cramped, their spot at Cité-des-Hospitalières allows them the space to spread their wings. They offer free weekly yoga classes, as well as a Storytelling Through Dance class for children, with more on the horizon.

“[I] just told my team that I want to launch a project where we'll be reaching out to the elderly women in our society, in our communities, especially from the marginalized communities, because they have the stories to share, but they never got an opportunity to share their stories. So we want to bring them back here, into this space, have them sit around the table and share their experiences. That oral history-telling, oral storytelling is almost recounting a history that has not been documented on paper. And those stories are very powerful to look at, but also, many of these senior citizens have not been approached to tell their stories; they have been dismissed outright. So those [are the] kinds of projects we are conducting all the time. We started a series called Interaction in which we allow the experts on certain important issues to interact with each other and with the audience. We had a discussion about the different shapes of feminism, how it might be different in the West versus in the East. And what are some of the concerns of LGBTQ community? LGBTQ discussions have almost become mainstream, and yet have we gone deep enough to understand the insecurity of that particular group?... Those discussions we are bringing in, [we] do not necessarily need to present a play on that, right? Just the authentic storytelling itself becomes a play.”

It's a distinction with a difference. The company sees itself as a living part of the community, a connection all too often lost in the Arts with a capital A.

“Professional art is very aloof from community engagement. They treat community only as an audience, as a paying audience. But that's wrong. The community is an instrument of change. We like to engage our community prior, during, and after the activity, not just as the audience but as a partner.”

To those who might be inspired to take up the cause of meaningful, community engaging art, Rahul sends his support

“I encourage them. In Canada, art is publicly supported. There is money for the art in the budget all the time, by act of Parliament. And that money has to be used for the public. So, why should we not do public art, which is for the public good? It isn't [fair] to say that there is no value in entertainment, of course. You know, if we begin to bore people, then they are not going to learn anything. But I think that the art and aesthetic, the politics and aesthetic are intertwined. They are not separate. One of the big problems in the world of the theatre, in the world of cinema, is that if it is political, it can't be art. That’s wrong. Aesthetics and politics are sides of the same coin. If they don't exist together, then we’ve lost the purpose.”

Closing out our conversation (and I promise, I could've chatted with him for hours), I ask Rahul if he's ever been scared of speaking his truth, or if there have been subjects even he felt were taboo to touch upon. No, he tells me calmly, his smile returning, his eyes dancing.

“I respect the democracy that exists in this country. I come from India, a country where there is severe separation, no freedom of speech, especially in today's time, when the internationalist government is suppressing any kind of progressive opinion…The critiques I raise are not to denounce Canada, only to make it better. But I respect the fact that we have freedom of speech. I respect the fact that Canada is a democratic state, that I have a right and an obligation to speak, and they have a right and obligation to hear. So I'm not afraid at all.”

Visit the Teesri Duniya Theatre Company website for more information on upcoming workshops, classes, and productions.